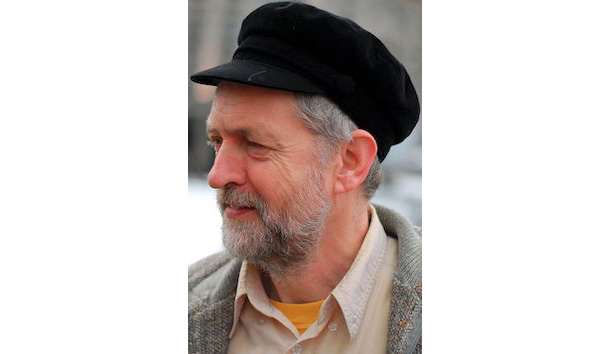

“Scarecrow,” an aged overcoat that saw its best days and owners generations ago, over which is thrown a hat of no known provenance but suggestive of a head underneath, the ensemble being draped over a stick. The idea is to frighten off the crows, but the smarter crows are not taken in and pillage the field around. The role of scarecrow is now assigned to the shapely form of Jeremy Corbyn, who is used by the Conservatives as the main reason for voting their way. To call this reasoning “spurious” would grant it a higher value than it merits. Labour in its present-day form is a beat-up Trabant party, wheezing and smoke-emitting, a menace on the roads. Its prime policy is to nationalize wealth. And yet it is held as the major obstacle standing in the path to the sunny uplands, whither the Tories promise to conduct the nation. They are the party of enlightened capitalism. Corbyn has no better friends than the Tories; he needs them, as they need him. It is a pact based on mutual disregard, welded into acceptance of role.

Into this agreeable set of usefully opposed values enters Nigel Farage, the owner—it is a company, not just a party—of the Brexit Party. He is the dark figure who breaks into the mood of the Watteau picnic, the duopoly. His message on the EU and Brexit is the clean break, and not the “deal” which is the unwavering objective of the establishment. The “deal” is of course a totally amorphous concept, which takes on the meaning determined by those who shape it. Never mentioned in the referendum, the “deal” is the primary weapon of those planning to overthrow the apparent result of the peoples’ decision. Theresa May fashioned her entire strategy around the “deal” concept, which meant keeping her negotiations under wraps until March 26th, 2019, when it came out that the departure date of March 29th could not be met. A policy that cannot succeed has infinite attractions. Such policies kept May in office for three years.

And now Farage has transformed the scene. His Brexit Party, with a huge number of parliamentary candidates in the wing, was a massive threat to the establishment. Immense pressure was then brought upon him to yield, and he then stated that Brexit would not field a candidate in all 317 seats held by the Tories. This, he claimed, was an unacknowledged pact (or what an actress lately termed being “self-partnered”). Farage then expected a reciprocal gesture from the Tories. It was not forthcoming. They simply wanted more, like Johnny Rocco in Key Largo, and are said to have been making remarkable offers through intermediaries for Brexit candidates to stand down. The current media line is to accuse Farage of Splitting The Conservative Vote, a high crime which could only end in the victory of the Corbynistas.

This is far from assured. Polly Toynbee, the doyenne of the Left, judges that Farage’s retreat is “shrewd.” He is now free to concentrate his party’s energies in the non-Tory constituencies of the North and Midlands, where Farage has been campaigning with zest. He may well win a few seats; he will certainly bite chunks out of the Conservative vote, with incalculable consequences. And there’s more. Last week the list of nominated candidates was made public. In Uxbridge & South Ruislip, Boris’s seat, there emerged a UKIP candidate, Geoffrey Courtenay. UKIP, a party thought to be all but dead, has now come to life. It is not part of Farage’s retreat from the 317 Tory seats and is free to fight its own battle. This, in Uxbridge, is far from forlorn. I have already alerted followers of this blog to the perils in that constituency, which can now take on more definition. The main threat to Boris comes from Labour, whose candidate, Ali Milani, is a Muslim immigrant who left Iran at the age of five. Between the general elections of 2015 and 2017, the Labour vote rose from 26.4% to 40%. In London, the alliance between Labour and the Muslim community is unbreakable. It is perfectly conceivable that it could unseat the Prime Minister.

Where does this leave a post-election “deal” that Parliament will accept? If the hostility to the Conservative plans continues, the numbers in the Commons may not allow a successful withdrawal. The UK departure from the EU stretches out into the future. It recalls Zeno’s paradox, of the ever-moving arrow that never reaches its target. As Tom Stoppard added, “And St Sebastian died of fright.”

Leave a Reply