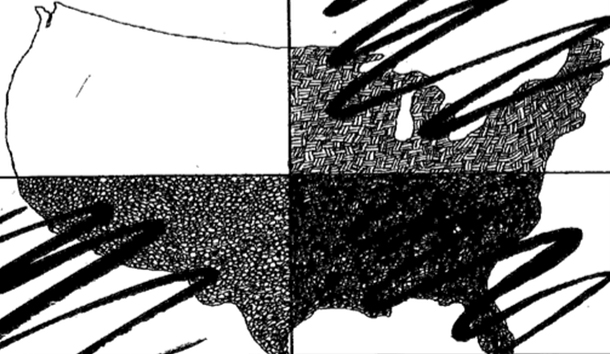

How different this country would be if we had a 28th Amendment which read: “An amendment approved by the legislatures of three-fourths of the States shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part of this Constitution.” Three-fourths of the states, if they desired, would then be able to change the Constitution without the approval of Congress and without a convention. This simple change would fundamentally alter American democracy. The people would be encouraged to come up with new solutions to our problems. Certainly we would have term limits and balanced budget amendments. We probably would not have federal judges supervising law enforcement and running state schools, prisons, and mental institutions. Nor would we have the unelected Supreme Court determining basic social and economic doctrine. Under the 28th Amendment, we could restore basic principles of federalism and return to a government which better reflects the values of the governed.

The merits of various proposed constitutional amendments are widely debated, but there is little talk about the amending process itself. That process, however, more than the substance of any proposed amendment, defines the nature of our democracy. Our democracy is one in which the people ultimately must determine the power and authority of the federal government. It follows that the people need to be able to amend the Constitution without—as presently required—first having to obtain the consent of the government they are supposed to be controlling. The current amendment mechanism, which led Lord Bryce to conclude in his 1888 study The American Commonwealth that “The Constitution which it is the most difficult to change is that of the United States,” is a strange compromise from the last days of the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. It reflects the unresolved differences between the Virginians, represented by James Madison, and the Hamiltonians—differences, of course, which remain unresolved today.

The Constitution currently provides for two methods of amendment: in one, Congress, by a two-thirds vote of both houses, may propose an amendment to the states that will become effective when three-fourths of the states ratify it—all 27 amendments have been adopted this way; in the other, Congress, upon application of two-thirds of the states, “shall call a convention which” may propose an amendment to the states which will become effective when three-fourths of the states ratify it. Under the first method, because Congress must propose the amendment, it is unreasonable to expect any reduction of congressional powers or the powers of the other two national branches. In the second method. Congress “calls” the convention, but the Constitution does not specify how the convention is to be organized or what powers it will have. Congress, in the call, has to provide for shaping the convention. The shape Congress gives it will, of course, affect the convention’s ultimate success or failure.

George Washington, in urging the adoption of the proposed Constitution in 1789, highlighted the “constitutional door” through which the people could amend the document. But, in operation, the Constitution has been very hard to change. Washington’s “door” has been a narrow passage because the failure to obtain two-thirds of the members of each house of Congress to approve the proposed amendment has, so far, ended the amendment process. Congress has proven a jealous guard at the door to constitutional amendment, always reluctant, after the earliest days of the republic, to propose any amendment for the consideration of the states that might limit Congress’ own powers. Of course, the fact that the Constitution is hard to change has opened an opportunity for the Supreme Court to twist and shape the document, as Jefferson said, as an artist shapes a ball of wax. Woodrow Wilson, in his 1908 book Congressional Government, noted that “The process of formal amendment was made so difficult by the provisions of the Constitution itself that it has seldom been feasible to use it; and the difficulty of formal amendment has understandably made the courts more liberal, not to say lax, in their interpretation than they would otherwise have been.” The Court’s interpretations have almost always added powers to the national government.

The recent odysseys of two proposed constitutional amendments, one successful after a journey nearly as old as the Republic itself and the other unsuccessful after a far more abbreviated existence, show how the present system—dependent on congressional action—thwarts the wishes of the governed. The most recent constitutional amendment, the 27th, was ratified in 1992 and prohibits a pay raise in Congress from taking effect until after an intervening election. Proposed by the First Congress in 1789 at the behest of James Madison as part of the original Bill of Rights, the amendment was ratified by six states by 1791 and then lay dormant for nearly two centuries. But in 1989, after Congress voted itself a 25 percent pay raise, the sleeper awakened. Thirty-eight states quickly ratified the Madison amendment, and it became part of the Constitution. Because of the historical quirk that the First Congress proposed the amendment without limiting the time allowed for its consideration, the American people were able to change the Constitution without having first to obtain the consent of the modern Congress, which was enjoying its pay raise.

By comparison, recent opinion polls show overwhelming public sentiment favoring a Balanced Budget Amendment. Nevertheless, Congress has consistently refused to send the amendment to the states for their consideration. Last year, the amendment was approved by a two-thirds vote of the House of Representatives, but failed by one vote to get two-thirds of the Senate. Senator Craig of Idaho, late in the debate, emphasized that the Senate was not being asked to “pass a balanced budget amendment; it was being asked to propose” the amendment to the “citizens of the country.” He noted that the senators who voted against proposing the amendment “said very clearly under all of the smokescreen and all of the excuses that the) gave for not voting for it—there were two fundamental things. They did not believe in the right of the states to control their central government, and they would not give the citizens of these states the right to choose that option. I think that is profound, and it is sad.” Similarly, Congress has refused to forward any term limit amendment to the states for their consideration.

The alternative of proposing an amendment by convention has proven itself to be only of marginal practical value. Supporters of two amendments, the 17th, direct election of Senators (1913), and the 19th, women’s suffrage (1920), did campaign for a convention. As the number of states applying for a convention approached the necessary two-thirds. Congress, to avoid the uncertainty of the convention route, bowed to the popular will and proposed the amendments under the first method. The states then ratified.

More recently, proponents of term limits, following their five-to-four defeat in the Supreme Court, have announced a campaign to get the 34 state applications necessary to require Congress to call a convention. They have accused Congress of a “clear conflict of interest” in failing to propose such an amendment. “No one sees a way to get term limits without states beginning to apply for a term-limit convention,” said Paul Jacobs, executive director of U.S. Term Limits. Because of Congress’ refusal to propose the amendment, term limits advocates are forced into the awkward position of calling for a convention they do not really want, in the hope that the process will again prod Congress into proposing an amendment.

Because of uncertainty over how the convention would be organized and what its powers would be, however, the second method is not a practical alternative to an obstinate Congress. Congress continues to play a key role in the process, having been given the sole authority to call a convention. Because the Constitution does not specify how the call is to be made and what directions it should contain, a reluctant Congress may well establish methods of delegate selection or define the scope of the convention so as to reduce the chances for approval of any amendment unsatisfactory to Congress. Madison criticized the “vagueness” of the language during the 1787 Convention: “How was a Convention to be formed? By what rule decided? What the force of its acts?” Madison’s questions remain unanswered. A hostile Congress, in calling the convention, could easily take advantage of the vague language to impose procedures that indirectly sink the amendment.

A new, third method of constitutional amendment is needed that will bypass altogether the requirement for congressional approval or a congressional call for a convention. By allowing the states, without the approval of Congress, to control the amendment of the Constitution, we could restore the bargain between the states and the federal government that was the heart of the initial constitutional structure. Any state could propose an amendment, such as one providing term limits, and, if three-fourths of the states agreed to the language, the amendment would become a part of the Constitution. The people, acting through their states, would be able, through an orderly and manageable process, to reclaim powers previously granted to, or assumed by, the federal government.

Constitutional reform under this proposal would remain a deliberative process. The only change is the recognition of who wields ultimate control over the process. By allowing the states to consider constitutional amendments that have not been approved by Congress, we would alter fundamentally the existing relationship between the national government and the people. At the same time, we would restore the type of constitutional door envisioned by Washington and Madison at America’s birth. Since all just power is derived from the consent of the governed, the Constitution should be subject to amendment whenever the people believe the national government has aggrandized power and abused it. The states, after all, are closer to the people and more likely to reflect the values of the governed.

Why is federal control over the amendment process only now, after more than 200 years, manifesting itself as a problem? There are two answers. First, as long as state law controlled many of the important issues of the day, any deficiencies in the federal constitutional amendment mechanism were of little concern. As the federal government has asserted constitutional authority, however, to control more and more fundamental social and economic issues in the past several decades, shifting the original constitutional bargain at the expense of the states, the issue of who controls the Constitution itself has become more immediate and vital. Second, although the deficiencies of the current system may only now have become critically urgent, the vital role of the amendment process in determining the balance of power in the federal system was clearly understood by the drafters more than 200 years ago. Reports of the Constitutional Convention suggest that the current amendment process was agreed upon only out of political necessity and that the leading figures of that day recognized precisely that it would give tremendous power to the central government.

The loss of state influence over the shaping of significant social and economic policies is a phenomenon of the past 30 years. The states started to decline in influence during the period of the civil rights movement. “States’ rights” became associated with efforts to sustain the segregationist laws of the South, and any effort to assert the influence of the state in shaping matters of policy became “racist.” State government has since been relegated to the role of a largely irrelevant anachronism on the political landscape. Social and economic policies are now shaped by Presidents and by federal courts and legislatures, with little meaningful input from the states. The variety of debate at the local level has given way to a single debate—carried on in a strange language—at the national level. The opportunity for creative solutions to arise at a local or state level is sacrificed in the move toward central authority. The states, if power were restored to them, could provide 50 potential solutions to national problems instead of one. Some solutions would, of course, prove better than others. But at least the states provide a proving ground for experimentation, with successes verified and mistakes identified, before the entire nation is led down the wrong path.

The content of the national debate has come to reflect less and less the values of the governed. Frustration with the course of policies pursued by the federal government and the inability to alter that course has led the American public to question whether the authority of the federal government is subject to the will of the people. Much energy has been spent during the past decade to devise mechanisms that would limit the influence and access of special interest groups in the federal forum, in the hope that such efforts might restore the responsiveness of government to the wishes of the governed. But those efforts have been largely in vain. We cannot correct the perceived abuses by lobbyists unless we recognize that they are rooted in the growth of the federal government and its regulatory powers and the withering of any countervailing power.

The 1994 elections offer some hope that through the electoral process the majority can still demand the attention of their representatives in the legislature. But the federal power is bureaucratic and judicial, as well as legislative, and the majority has yet to find responsiveness in many of the most powerful halls of federal government. The solution to the current unresponsiveness of the federal government is not a simple matter of securing greater access to the federal system; we shall also have to restore the fundamental balance of American federalism and return to the governed the ability, acting collectively through their states, to control the development of fundamental national social and economic policies.

The idea is not a new one. Indeed, history tells us that a method for amendment without congressional approval very nearly became a part of the original Constitution. The Articles of Confederation had required that Congress first agree to any amendment, which then had to be unanimously approved by the states. When the 1787 Philadelphia Convention met, it had to decide (1) if the Constitution was to be amendable and (2) if it was, how it was. The first question was easily decided since, as Federalist No. 78 put it, it is a “fundamental principle of republican government which admits the right of the people to alter or abolish the established Constitution.” But the second question split the convention along its basic philosophical fault line. Gouverneur Morris wrote in an 1811 letter to Robert Walsh that the convention turned on “the necessity of drawing a line between national sovereignty and State independence . . . ‘that, if Aaron’s rod could not swallow the rods of the Magicians, their rod would swallow his.'”

James Madison, as he approached the Philadelphia Convention, emphasized the need to allow the states to limit the federal government without the consent of Congress, and he came within two days of having that authority included in the Constitution. The Virginia Delegation to the convention was clear from the start that amendments should be made whenever “necessary” and that Congress should have no role in the amending process. The Virginia Plan, written by James Madison and introduced on May 29, 1787, argued in Resolution 13 “that provision ought to be made for the amendment of the Articles of Union whensoever it shall seem necessary, and that the assent of the National Legislature ought not to be required thereto.”

The Virginians believed the states created the union and by the Constitution delegated express and enumerated powers to the federal government. In addition, power at the federal level was divided, with the executive, legislative, and judiciary powers to be separately and independently exercised. Madison and Jefferson believed they had created a federal government with limited powers. If the central government started to exceed its powers, the states, by amendment, could call it back. Of course, the government exceeding its powers would not consent to limit itself.

The Hamiltonians, on the other hand, believed that Congress should control the amendment process. Alexander Hamilton insisted on congressional approval of proposed amendments or the calling of a new Convention because of his basic bias in favor of a strong central government, and had no doubt that the states would use the amendment process to increase their power. As he told the Convention on June 22, 1787, “state government will ever be the rival power of the general government.” He intended that the states, once they created the national government, would not be able to control it.

Hamilton was correct that the amendment process would determine the nature of the central government. The harder to amend, the stronger the central government created; the easier to amend, the weaker the federal government and the more responsive it would have to be to the governed. By amendment, any decision of the national government—by the Supreme Court, Congress, or the executive—can be modified or overruled. Any power claimed by the national government can be reclaimed by the states and people. The amendment process was, therefore, a critical battlefield in the war between the Virginians and the Hamiltonians. It remains so today.

When the Virginia Plan came to the convention floor, Madison noted that “several members did not see the necessity of the Resolution at all nor the propriety of making the consent of the National Legislature unnecessary.” Colonel George Mason of Virginia responded that amendment was a necessary alternative to revolution and noted: “It would be improper to require the consent of the Natl. Legislature, because they may abuse their power, and refuse their consent on that very account.” After the initial debate, the Committee on Detail proposed that “On the application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union, for an amendment of this Constitution, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for that purpose.” This seems to have been a mangled attempt to compromise the differences between the Virginians and the nationalists. The proposed article, on the surface, provided for a state-initiated procedure in which the congressional role seems ministerial, i.e., that it “shall call a Convention for that purpose.” The problem, of course, was that the congressional role would not be purely ministerial since, by the call. Congress could control how it would be made up, how it would operate, and what the convention could do.

The Virginians apparently realized the problems built into the proposed article since the next version corrected them. The Committee on Style reported a new article providing that “Congress, whenever two-thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary, or on the application of two-thirds of the Legislatures of the several States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution.” The language required that Congress send to the states for ratification any amendment proposed by two-thirds of the states. At this point, Gouverneur Morris of New York and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts moved to change the state-initiated method to require Congress to call a convention rather than simply pass the proposed amendment to the states for their consideration. The added requirement of a convention changed the state-initiated procedure from a straightforward one controlled by the states to one so uncertain and complicated that it has never been used. Madison accepted the Morris-Gerry motion. The states’ ability to propose amendments was effectively eliminated.

Madison knew that the last-minute Morris-Gerry motion seized from the Virginia delegation a victory almost within its grasp. But, as George Washington wrote two days later, “The Constitution, which we now present, is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.” The Virginians had to compromise for what they saw as the greater good.

But they certainly would not have agreed with the Federalist Supreme Court Justice, Joseph Story, who praised Article V as an effective “safety valve” in his 1833 treatise, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. The “efficacy of a safety valve,” responded the 19th century scholar Sidney Fisher, “depends on the promptness with which it can be opened and the width of the throttle. If defective in either of these, when the pressure of steam is too high the boiler will burst.” Article V, Fisher concluded, is an “iron fetter” rather than a safety valve. The heart of the problem, of course, is the self-defeating consent mechanism which requires the body to be limited to agree that it should be limited.

Only in America, Tocqueville wrote in 1835, have the people acknowledged the right of judges to declare laws unconstitutional. In France, the constitution is supposed to be immutable, and the received theory is that no power has the right to change any part of it. In England, the constitution changes continually, or, in reality, does not exist, because Parliament is at once a legislative and constituent assembly. Whatever it enacts is constitutional.

French judges, on the surface, have more power than American judges, since they have the right, and they alone have the right, to interpret a constitution which cannot be amended. But as Tocqueville notes, were they to exercise the right to declare laws unconstitutional, they would encroach on rights more sacred than their own, namely those of the society in whose name they are acting. “[N]o danger of this kind is to be feared” in America, Tocqueville concluded, because “the nation can always reduce its magistrates to obedience by changing its Constitution.” However, Tocqueville turned out to be wrong; because of our flawed amendment process, Americans are not able to reduce magistrates to obedience.

Madison in Federalist No. 43 wrote that a Constitution could be too “mutable,” on the one hand, or, on the other, so hard to change that we “perpetuate its discovered faults.” A constitution that cannot be made to conform to the values of the governed may lead to revolution. A new constitutional convention, while it may lack the violence, terror, purges, and guillotines of a revolution, certainly threatens, and could produce, a different society. Most people do not want a revolution or a new constitutional convention. But they do believe that basic revisions of the Constitution could bring Congress and the Court under control. The patch, Jefferson said, should fit the hole, and the proper patch in this case is the state-initiated amending process which Madison originally proposed.

Jefferson wrote that the basis of our experiment is that “men may be trusted to govern themselves without a master.” Madison said that all “our experiments rest on the capacity of mankind for self-government.” If they are wrong, America is wrong. Self-government means the citizen is free to act, and the Madison version of Article V allows for such freedoms. If three-fourths of the states want to change the Constitution, they should be able to do so.

Leave a Reply