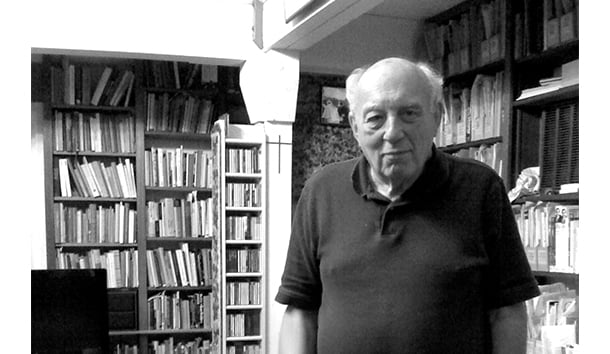

When long-time Chronicles contributor John Lukacs died on May 6, the country lost one of its finest adopted sons, who was also one of its finest writers and historians. The scope and extent of his work defies summary—he published over three dozen books between 1953 and 2017 on a wide-ranging list of subjects, including: the philosophy of history, World War II, the Cold War, Tocqueville, George Kennan (a longtime correspondent and personal friend), Agnes Repplier, democracy, nationalism, a half-century of Philadelphia’s cultural landscape, and his own life and experience.

His life was defined by his deep scholarship. In its obituary, the New York Times quoted a self-reflective statement from one of his final columns for Chronicles, in 2017: “I am a crumbling remnant. A remnant of the very end of the Bourgeois Age and a remnant of the Age of Books.”

When I first encountered the great historian’s byline in Chronicles some twenty years ago, so lucid and limber was his prose that I assumed he must be a remarkable young scholar just entering the prime of his years. Imagine my surprise when I soon learned he was already in his 70s, retired after 47 years of teaching at Chestnut Hill College. Yet in a sense he was indeed in his prime—soon after I first read him he published the book for which he is probably best known today, Five Days in London, and new works continued to appear almost annually for the next dozen years.

Lukacs lived to see Five Days in London became the basis for the film “Darkest Hour” in 2017, though the movie was less than fully faithful to Lukacs’s account of Winston Churchill’s mentality and actions as he decided whether to continue the war with Germany. Lukacs’s book had become a bestseller after 9/11, when New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani recommended it and compared the experience of the attacks on the Twin Towers to living through the Blitz. Despite the recommendation, Lukacs did not excuse the mayor’s hyperbole—he responded that the jihadist attack, horrific as it was, was not comparable to the sustained onslaught that London had faced from Hitler.

Lukacs drew equally sharp distinctions between Churchill and a latter-day American “war president” like George W. Bush, whose adventurism Lukacs condemned. He had long criticized the blending of military symbolism into civilian politics, such as the practiceof civilian leaders saluting to soldiers. The title of his 1984 book, Outgrowing Democracy, was a warning about where he saw America heading. A refugee from the Soviet domination of Hungary—and before that, a conscripted laborer under the Nazis—Lukacs was an enemy of totalitarian ideology. But he saw nationalism itself as a more powerful force than any empire of the mind. This led him to agree with Kennan’s assessment of the Soviet threat as one that could be contained. And it led him to predict the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself, at a time when the CIA and the anti-Communist intellectuals of the conservative movement believed the Cold War would continue indefinitely.

I would have spared myself some embarrassment years later if I had applied Lukacs’s insights correctly myself: on the eve of the Russian seizure of the Crimean peninsula, I confidently predicted that Vladimir Putin would never attempt such a thing. Lukacs had more than once written that for Russia—under any of its regimes in modern history—security has always been largely understood in terms of land. Economic leverage over Ukraine, which Russia certainly possessed, and the prospect of extorting cooperation through military intimidation were simply not good enough—the land itself was the only guarantee of Russian interests, in Moscow’s characteristic calculation.

Lukacs was an old-world gentleman and a gentleman-scholar: he wrote to be read, a purpose that extended even to his footnotes, which were never merely a scholarly apparatus. They adorned the page not just to provide citations but also to offer new thoughts and digressions, in prose every bit as polished as that of the main text. Whether writing memoir (Confessions of an Original Sinner) or about the history of philosophy (Historical Consciousness), whether examining a short period (Five Days in London) or the better part of a century (A New Republic: A History of the United States in the Twentieth Century), Lukacs crafted his prose with the reader in mind. His were books for a literate public, of whatever size that public might be.

Among his many insights was his verdict that Woodrow Wilson, not Vladimir Lenin, had been the greatest revolutionary of the twentieth century. Indeed, Wilsonianism has outlived Communism, and the legacy of the popular nationalism that Wilson professed to champion is a force with which the world still grapples today. In his 2005 book Democracy and Populism: Fear and Hatred, Lukacs made unmistakable his grim judgment against nationalism and populism, whichmight seem to put Lukacs out to step with the mood of the United States and Europe today.

In fact, Lukacs was an outspoken foe of nationalist politics long before Donald Trump, and many of his paleoconservative admirers were pained to see him deplore Pat Buchanan. But readers of Lukacs can understand, as Lukacs himself certainly did, that nationalism is a force that cannot be wished away. Whether it can be turned to constructive ends, and its destructive tendencies curbed, are questions that the rising generation must answer. The works of John Lukacs show vividly what is in store for those who get the answers wrong.

Leave a Reply