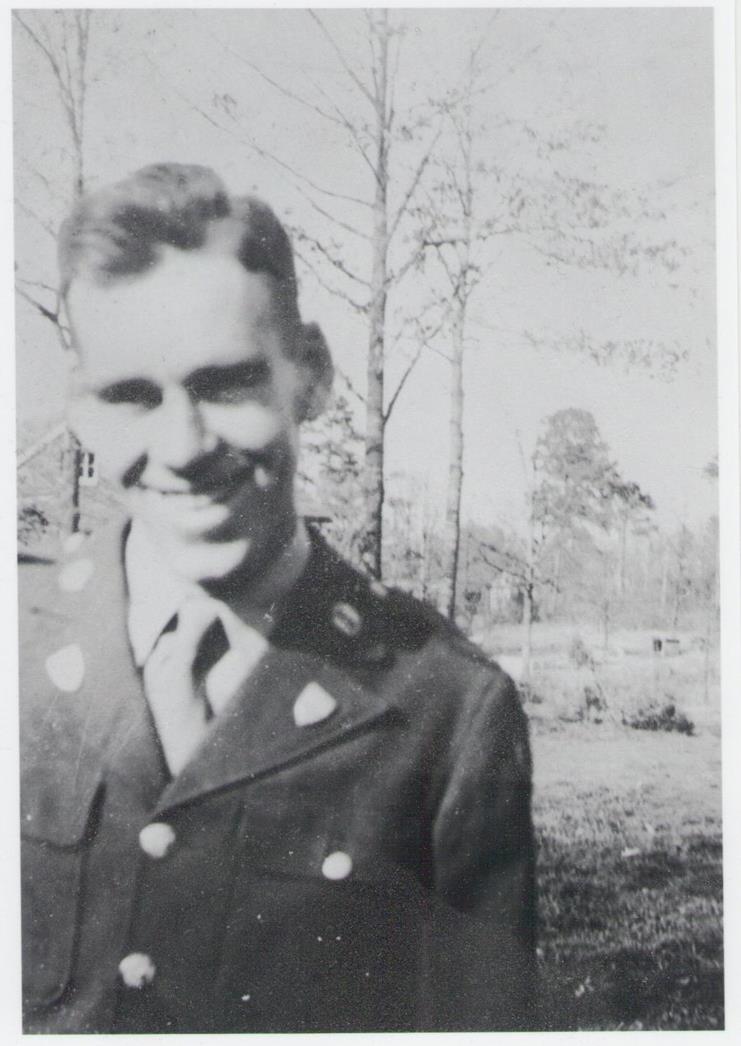

My father, Harry S. Cathey, was a World War II veteran. He left behind letters to my mother written from France and Germany in 1944 and 1945. Some of the words and designations are obviously in a code they had between them—he could not identify locations in the combat zone. What comes through above all are two things: his sense of duty to his country and his abiding love for my mother—no real complaints about his conditions, although he does express the wish that he can taste her cooking again and, of course, the hope to see her soon.

A member of the 101st Cavalry, my father was assigned to a Stuart light tank and was involved in reconnaissance operations. On March 15, 1945, near Kaiserslautern in the Rheinland-Pfalz, his tank was hit directly by a German projectile. Dad, then piloting the tank, was seriously wounded, and his best buddy Dale Lackey, the gunner, was killed.

Shortly before the attack, my father and Dale had traded positions: for several days previously, my father had been the gunner and Dale the pilot. They often switched positions—and they had done so only hours before the fatal incident. That trade had saved my father’s life, almost miraculously, just as it had taken Dale’s. This fact has always affected me deeply and impelled me to count my blessings.

After the war and after my father got out of Walter Reed Hospital with a permanent back disability, he and my mother went to Granite Falls, North Carolina, to visit Dale Lackey’s widow. When I was born several years later, I received in Dale’s honor and memory the middle name “Dale.” Throughout my life I’ve carried the name of the man who perished in the place where just as easily my father could have been. Thus, Memorial Day is always significant for me, for I honor especially my father’s service and the memory of his buddy, Dale Lackey.

Some 75 years later, I’ve decided to search out any living members of the family of my father’s compatriot. I located Stephen Dale Lackey, of Statesville, North Carolina, born Dec. 8, 1944—the son that my dad’s buddy Dale would never see. I contacted him and told him about my middle name in honor of his father, and how that change in tank positions saved the life of my dad. As we talked by telephone I think we were both deeply moved as we realized how war can radically alter destiny and lives, not just of its direct participants but also of their families.

Observing Memorial Day in 2020, like millions of other Americans, I recall the sacrifices of those who fought in wars in far-off countries. Some remain in neatly kept cemeteries in France or other venues. In many cases, those men did not understand fully why they were engaged in conflict, save that their country had called them to do so. Like my dad and Dale Lackey, it was their duty.

Through all this country’s military conflicts, more recently through Vietnam, and then the Balkans and the Middle East, American boys, fathers, sons, and brothers have answered the call.

In 1941 it was easier to make the case that our young men must answer that call. After all, for whatever reason, we had been attacked, and we had no other option than respond and respond forcefully, to mobilize and prepare for years of grueling and painful war. But there have been other conflicts—in Bosnia, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, etc.—which remain extremely controversial.

Consider the Spanish-American War, arguably a case of American imperial adventurism against Spain. And U.S. involvement in World War I is increasingly recognized by historians as a monumental error, with disastrous consequences for everyone involved. The victory of the Triple Entente (i.e., Great Britain, France, and Russia) and the resultant draconian peace, hugely facilitated and made possible by American intervention, set the stage for the rise of world communism and the accession to power in Germany in 14 short years of Adolf Hitler.

And there is a mound of evidence now indicating that Franklin Roosevelt, eager to enter the war in Europe on Britain’s side, took actions that propelled the Japanese into war, making the Pearl Harbor attack all the more likely. Historian Charles C. Tansill calls those steps “the back door to war.” Historians and authors still hotly debate those assertions.

Men like my father and Dale Lackey are called “the greatest generation,” and the reasons that are given are that they “saved us from totalitarianism,” or “they defended democracy,” or “they made the world safe.” In retrospect, maybe a lot of that is questionable, self-justifying propaganda…but always with an embedded, fragile, often obscure kernel of personal truth.

They were not political strategists or encumbered with high positions in government where long-range policies were made. Perhaps if they had been, things might have been different.

Those men did their duty, experiencing the pain of separation, the privations of war, the many necessary sacrifices, and oftentimes death. In this they leave their memory and honor to us all, unselfishly.

And, so, we honor them, we remember them—at times our hearts still ache as we recall them in our presence, as we recall listening to their voices and stories, and as we admired and continue to admire their hard-earned and often weary wisdom.

That is, in so many ways, the real “why” of Memorial Day.

Image Credit: Boyd D. Cathey’s father, Harry.

Leave a Reply