The great and good French novelist and thinker Jean Raspail died on June 13, three weeks short of his 95th birthday. I was deeply saddened by the news, although at his age it was to be expected. It is ironic that he succumbed to the COVID-19 virus, the product and totemic symbol of our age and the globalized world, both of which he loathed with a passion.

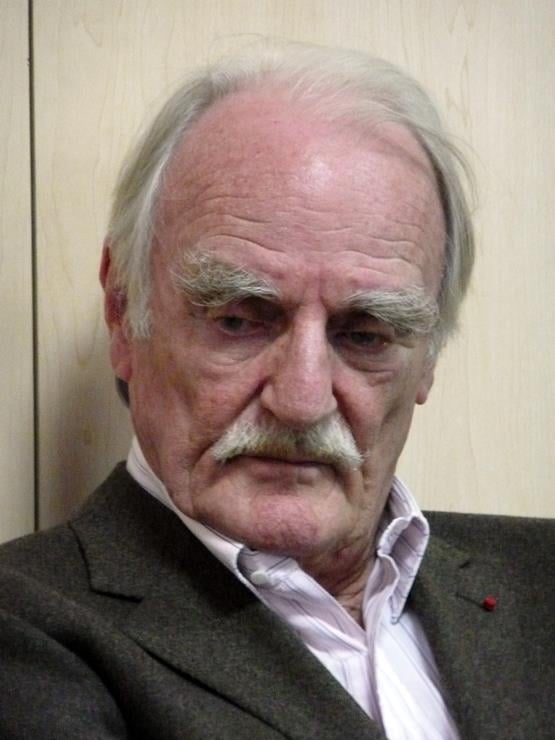

His bookcase-lined study felt a tad melancholy when I entered it, for the first and only time, in the summer of 1993, courtesy of General Pierre Gallois. It brightened soon enough with the host’s easy bonhomie, single malt Scotch (that was a surprise, I expected cognac), strong tobacco, and lively conversation. Raspail did not look very French to me. He seemed the embodiment of a Nordic patrician with his military mustache, a regular and austere face, a straight and remarkably slim figure. He was 68 at the time and looked 10 years younger. He evoked the image of ancient warriors whose blond hair turned red in the light of the Hyperborean campfires.

I was an awed 38-year-old aficionado, having read The Camp of the Saints in English translation some years previously. It was one of the few books that profoundly marked me for the rest of my days, on par with Dostoevsky’s Demons, Malaparte’s Kaputt, Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night and Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology.

In Camp of the Saints, his best-known work, Raspail castigated the “submersion” of France by the landing of a fleet of derelict boats from India loaded with refugees. The rest of the grim story is known to Chronicles readers, or should be. “We must reread The Camp of the Saints, which, beyond evoking with a talented pen the migratory perils, had—long before [Michel Houellebecq’s] Submission—mercilessly described the submission of our elites,” tweeted Marine Le Pen in tribute to Raspail. In addition to his resolute stand against all Third World—but especially Muslim—immigration, and in line with his traditionalist understanding of Catholicism, Raspail condemned communism and capitalism with equal force, as the two monstrous twins born of modernity.

The first thing I spotted on his desk was an ax from the steppe, a magic artefact from a mythical past, as it turned out, and an inspiration for one of his novels. The walls uncovered by books were filled by marine paintings, badges, and bottled boats.

Raspail and I smoked while the others discussed politics in French. Only as we were about to depart, Raspail turned to me, General Gallois’ Serbian friend, and stated point-blank that “in Bosnia your people are defending Europe from Islam, not for the first time.” The general agreed, having authored a seminal chapter about the wars of Yugoslav disintegration earlier that year. This matter-of-fact statement was music to my ears, but not surprising coming from Raspail.

Born on July 5, 1925 in Chemillé-sur-Dême, in the western department of Indre-et-Loire, Raspail studied at the private Catholic Collège Saint-Jean-de-Passy in Paris. One of his professors there was Marcel Jouhandeau, a prominent Catholic writer who was a lasting influence on him. The young Raspail was already trying to write, but chose to widen his geographical horizon first. In an early adventure in 1949, he paddled from Quebec to New Orleans in a canoe via the Great Lakes and rivers. In the ’50s he travelled, mostly by unconventional means, from Tierra del Fuego to Japan, a country he respected immensely and where he spent a year in 1956.

Each trip cemented Raspail’s considered opinion that modernity brings men only sorrow and disillusionment. This went hand-in-hand with Raspail’s sympathy for the fate of the last of a long but defunct line, in Patagonia, the Caribbean, or Central Asia. He knew, as well as those affected, that they are doomed and that there was no need for much ado. On that much, the antimodernist Frenchman and the stoical natives from the end of the world could agree.

The image that Raspail’s other obituarists have created is that of a reactionary and royalist. That is not altogether wrong, if we define “reactionary” as someone who wants to return to an earlier and better state of affairs. Raspail refused—according to his own words—to “enter the 21st century,” deeply disdainful as he was of the previous one. He defined himself as “a free man, never subservient to a party, never subscribing to received wisdom, always ready to patrol the edges.” By faith he was a “pagano-Christian.” “Hey, Catholicism,” he once exclaimed, “we have to keep the best of paganism, right?”

In his final years—almost five decades after publishing his prophetic dystopia—Jean Raspail was resigned that our civilization is on the “road to disappearance.” As he explained in an interview published in Valeurs Actuelles in 2013, he had no desire to join the massive circle of intellectuals who spend their time debating immigration because, in his view, such talk is useless:

The people already intuitively know that France, as our ancestors shaped her over the centuries, is on the road to disappearance. The audience is being kept amused by endless talk about immigration, but the final truth is never stated. Furthermore, that truth is unsayable, as my friend Jean Cau had noted, because whoever says it is immediately hounded, condemned, and then rejected. Richard Millet came close to that truth, and just look what happened to him!

Richard Millet was a prominent figure in French literature who lost his job and was hounded out of public life because he claimed that Anders Breivik, the Norwegian mass killer, was a normal product of multiculturalism.

What can be done? Raspail’s verdict was clear:

There are only two ways to deal with immigrants. Either we accommodate them, and France—her culture, her civilization—will be eradicated without so much as a funeral. In my view, that is what is going to happen. Or else we do not accommodate them at all, which means we stop sanctifying the Other and rediscover our neighbors.

Jean Raspail will be sorely missed by all Frenchmen and other Europeans who refuse to go gently into the multicultural night.

Image Credit:

French writer Jean Raspail on September 25th 2010. (Ayack/Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply