For more than 60 years, I’ve been interested in both the historical past and in how historical interpretations are created. I’ve also written a great deal on both subjects, but particularly on how public and scholarly opinions about past events and personalities change, and why they change. I believe there are two routes through which historical interpretations change over time: a natural, methodological path or an ideological one. The first is similar to the process used in the hard sciences. It involves pursuing research and arriving at the conclusion that what one had believed was based on inadequate information. This path requires one to look deeper to discover, as the 19th century German historian Leopold von Ranke expressed it in his memorable German phrase, “wie es eigentlich gewesen”—how it really was.

Of course, we can never arrive at a complete understanding of the past. However, historians should still aim for that ideal. English historian Herbert Butterfield said that Ranke’s ideal of “objective history” was useful—not as something that we could ever achieve totally—but as something scholars should strive to approximate. Moreover, even if our personal politics might make us lean in one direction on a subject about which we have strong feelings, it is our duty to put our prejudices aside when we investigate historical data. For example, when I wrote a book on fascism, I found myself often agreeing with the Marxist interpreters of the history of the rise of fascism. Although I’m opposed to Marxism and its interpretations on other matters, on the subject of fascism I had to be willing to recognize truth where I found it. On the other hand, despite an effort to be objective, I have never encountered any new truth about the past from reading LGBT activists or the authors of so-called feminist histories.

In contrast to Ranke’s and Butterfield’s ideal, there is a second approach to revising our understanding of the past, and it is centered on bolstering a political cause. This second path has grown so dominant in our age that it has come to overshadow the first path. Our present ideologically driven historical narratives tend to go in one direction only: toward the condemnation of whatever Western civilization was before the advocates of intersectional politics culturally and educationally conquered it. Historical studies in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe seem to be driven more and more by a passion to tear down what was believed to be good about Western societies before the second half of the 20th century. It is not that the authors of such histories never say anything that is true. But what is true in their narratives can be found in other more traditional historians before our cultural revolutionaries left their brand on the historical profession. I am also not saying that all critical studies of the past take the second path. What I am most definitely claiming is that what today is the dominant form of critical history reflects the ideological direction described.

Another feature of ideological history is the effort to make normal people feel guilty about the real or alleged discrimination that supposedly is peculiar to the Western Christian past. This is what I refer to as “penitential historiography,” and it aims at arousing moral uneasiness in the reader. Reading these ideological revisionist accounts, one is falsely led to believe that non-Western societies never engaged in hateful practices, such as practicing slavery. We are further assured in today’s college classes that traditional Muslim or African tribal societies showcased modern leftist ideals. Indeed, these societies are depicted as the precursors of what our leftist establishment is now seeking to achieve for us. Only Western peoples need to be scolded for not fitting the bizarre egalitarianism of our current academics and journalists.

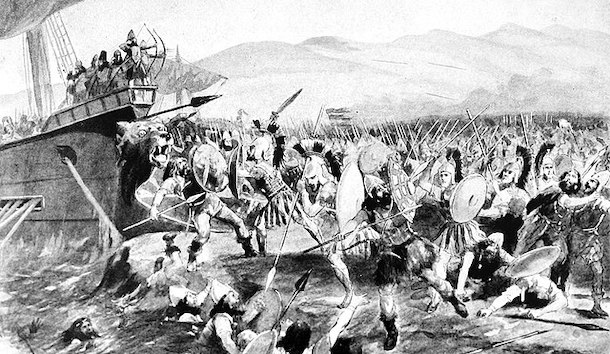

Allow me to note that I learned more solid history from taking European and American history in my high school in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in the late 1950s than I ever picked up from progressive historians. At Bassick High School in Bridgeport my teachers provided factual history, and I was able to build on what I learned from their classes. When my high school teachers discussed conflicts among ancient or modern people, they would try to be fair to both sides. Although we were living in Connecticut, not South Carolina, my teachers tried to clarify the grievances of both North and South in laying out the causes for the American Civil War. Unlike such anti-Southern conservative commentators as Allen Guelzo and Karl Rove, they regarded the soldiers in both blue and gray as true Americans, and the bloodbath they were engaged in as tragic. My teachers did periodically depart from the ideal of objectivity in cases where it was warranted, such as in describing Hitler and Stalin as bad actors. I also recall hearing my history teacher characterize the Athenians and Spartans as “our ancestors fighting for our civilization” when the Persians invaded their homeland. But this outburst of enthusiasm seemed fine to our class and still does to me now. I would prefer hearing someone identify with our classical heritage than a feminist scold berating ancient Greeks or my parents’ generation of Americans as sexists or racists. In any case the ancient Greeks were fighting for what became our civilization before the political left managed to pollute and denature it. And I’m overjoyed they prevailed at Marathon and Salamis.

Leave a Reply