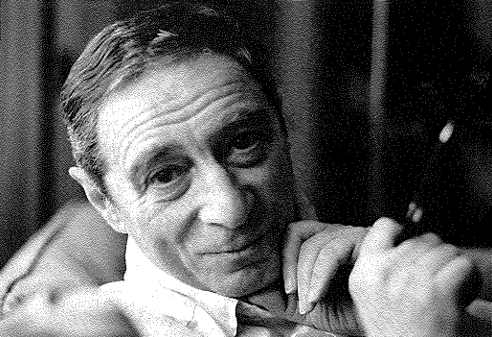

I am honored by the invitation to reflect with you on the life of our friend and colleague Leopold Tyrmand. There are those here who knew Leopold longer and better than I. But in the last several years I came to know him well enough that I am not surprised by the remark of one journalist who, upon learning of Leopold’s death, said, “Until I met Leopold Tyrmand I could not have imagined the existence of such a mind.”

A remarkable mind he was, but Leopold was much more than mind. Ideas and words were his matrix and his medium, but his project was nothing less than living well. Speaking to the Philadelphia Society two years ago next month, Leopold surveyed, in his inimitable style, the wreckage of what he insistently called “liberal culture,” and he asked the inevitable question, “What is to be done?” “My answer would be,” he said, “first, refurbish our prescription for how to live a rewarding life.” How to live the rewarding life—it was this that Leopold sought to understand, to communicate, and to exemplify.

Leopold’s life was marked by driving moral vision and by whimsy; by sardonic humor and by rage. He cared enough about others to be outraged that they cared so little about themselves and what they were doing to themselves. Under the totalitarianism of the Nazis and then of the Soviets, he had been schooled in the fragility of those things that make for the rewarding life. Because he had been at the margins of life he had come to understand what is at the center of life. He was outraged by a culture that not only did not see that the center was not holding but took adolescent delight in its collapse.

Leopold’s outrage was gentled by those who centered his own life. Above all, Mary Ellen and a marriage that he once described, paraphrasing the Apostle Paul, as a gift to one born out of time. And the children. John Howard tells me this was usually Leopold’s first news of the day, some new thing the children had done. If Rebecca had made some dramatic gesture for the first time, it was sure evidence that she is a budding Sarah Bernhardt. Matthew’s athletic leap from the sofa was certain portent of his future fame as an Olympic champion. For the children, most of all, Leopold did not live as long as he should have. But we may pray that he watches over them still, and will see them realize the immensity of the hope that he invested in them. And as their mother will make sure they never forget, he leaves to them a legacy beyond earthly riches, the knowledge of a father who sought to exemplify the rewarding life.

Leopold’s life was centered also by friendship. I know only in small part all the years and all the labors that John Howard and others here shared with Leopold in The Rockford Institute. The planning and the dreaming, the disappointments and the triumphs; in this moment you can in memory touch upon the velvet times of accord and the burlap times of disagreement, and it is all the texture of a rewarding life that you were graced to share, and I, in small part, with you. It seemed to me that for Leopold friendship was less a matter of sentiment than of companionship in a great cause. Nobody ever claimed that Leopold was the easiest person in the world to work with. Truth to tell, not many people ever accused Leopold of being excessively modest. But at the core of his being was a modesty more important than the modesty of demeanor. Leopold’s modesty was in his determination to be the servant of a great enterprise. It is a sign not of his immodesty but of his devotion that he dared to say—and to say again and again—that the great enterprise is nothing less than the reconstruction of Western culture.

Culture, freedom, faith—these were, so to speak, the three articles of Leopold’s creed and of his understanding of the rewarding life. Culture cannot exist except in freedom, and neither culture nor freedom can endure unless sustained by faith. Culture, Leopold said, is “the qualitative meaning of life.” Or, quoting a Polish writer of his generation, “Civilization is fork, knife, and spoon. Culture is how to use them.” Culture is style. And Leopold was determined to live with style. Not the style of ephemeral stylishness, but the style of an elevated life lived as though life had consequence. And the requisite freedom, far from being the freedom of license, is the freedom that is discovered in freely binding oneself to the normative. In Leopold’s vocabulary “normal” was not a dirty word. Whether in jazz or in literature or in friendship or in marriage, only the acknowledgment of the normatively normal can illuminate the astonishing variations which give vibrancy and luster to a great culture. It was an abiding lament of Leopold’s that so many conservatives who also wished to defend the normal are so very dull, so apparently devoid of a capacity for astonishment. For Leopold, conservatism was a cause of high adventure.

Culture, freedom, and faith. Leopold wrote and spoke often of the Judeo-Christian tradition as the utterly irreplaceable foundation of the culture he cherished and sought to serve. On doctrinal content he was, to my knowledge, somewhat reticent. But he declared himself to be sure that we are bound by a transcendent truth, a truth prior to and external to ourselves, and he believed that that truth is ultimately both just and merciful. He said there is a “recompense” built into the nature of things. In that faith he offered up himself and his work. Leopold concluded a 1982 speech by asking whether we would achieve the cultural reconstruction for which he labored. He answered, “As my most trusted American philosopher, Fats Waller, used to say, ‘One never knows, do one?'”

Now the earthly chronicles of Leopold draw to a close, and we can express the hope that now he does know, and he knows that he has not labored in vain. He has not labored in vain, not least of all, because we, his family, friends, colleagues, in commending him to the just and merciful God, recommit ourselves to the rewarding life that he sought to exemplify—the life of culture, of freedom, of faith.

Leave a Reply