Sometime during the last decade, the Philip K. Dick cult came out from underground. Those of us who spent the 1980’s trying to explain our affection for this pulp writer no one else had heard of, this author of surreal science fictions and bleak realistic novels, have watched both pop culture and the academy discover and embrace his darkly comic work. Rock lyrics allude to his plots. Films—four so far: Blade Runner, Total Recall, Confessions d’un Barjo, and Screamers—are adapted from his stories. Tenured literary scholars investigate his books; in France, they gather at annual conventions. His face graces the cover of the New Republic, and his life and ideas are discussed (ineptly) in the Weekly Standard. His ghost is occasionally sighted, Elvis-style, by credulous fans. His name has become, as one friend puts it, “the ungainliest adjective in the language”—as in, “this Phildickian situation.” Anyone who has read Dick will understand the expression.

Most articles about Dick in the popular press quickly launch into a list of essential titles, typically Time Out of joint (1959), Confessions of a Crap Artist (written in 1959, published in 1975), The Man in the High Castle (1962), Martian Time-Slip (1964), The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1966/1968), Ubik (1969), Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said (1970/1974), A Scanner Darkly (1977), VALIS (1978/1981), and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982). The writer will then add a few favorite titles of his or her own—I myself am partial to Mary and the Giant (1953/1987), We Can Build You (1962/1972), Now Wait for Last Year (1966), and Galactic Pot-Healer (1969). There is a lot to be said for this approach: Dick could produce polished prose when given a chance, but more often was forced to support himself and his families by churning out novels at a breakneck, pill-fueled, inevitably sloppy speed. It makes sense to direct beginners to his most accomplished novels, lest they be turned away by, say, the incredible widening plot holes of The Penultimate Truth.

Yet the importance of Dick’s work ultimately lies not in any particular plots he spanned or characters he devised. Dick will be remembered for the vision that underlies his entire body of work: frightening yet funny, paranoid yet hopeful, with few barriers erected between the extraordinary and the apparently mundane. Dick wrote about the importance of maintaining one’s humanity even when trapped in inhuman situations. To that end, he created remarkably human protagonists, consciously avoiding the larger-than-life heroes who had dominated science fiction’s alleged Golden Age of the 1930’s and 1940’s. The archetypal Dick hero is a small businessman or bureaucratic functionary with a nagging wife and a nagging suspicion that the entire universe exists only in his imagination. The archetypal Dick plot will conclude with the protagonist discovering that he is wrong: the entire universe actually exists only in someone else’s imagination. Yet he will soldier on, and tend to his failing marriage, even as the cosmos collapses around him. In The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Earth faces a Satanic invasion from outer space. As the very fabric of reality is infected by an evil alien presence, the foremost thought on our hero’s mind is whether he will ever reconcile with his ex-wife.

Which leads us to an important point. It is sometimes said that in Dick’s worlds, nothing is as it seems, but that is not exactly true. Your neighborhood may be a Potemkin village, your girlfriend may be a police agent, and your life thus far may be an implanted memory; a lemonade stand, on closer examination, may prove to be a piece of paper bearing the words “lemonade stand,” and the United States may, on closer examination, prove to be ancient Rome. But you still live in that neighborhood, and that girlfriend still loves you. The concrete bonds that people form are still real, even if none of those people are who they say they are. And the moment of divine insight is still valid, even if there is no God. (In at least two of Dick’s books, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and A Maze of Death, religions demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt to be frauds nonetheless work miracles. And in at least two more. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and A Scanner Darkly, men have affairs with women who turn out to be agents spying on them, but their love remains real.)

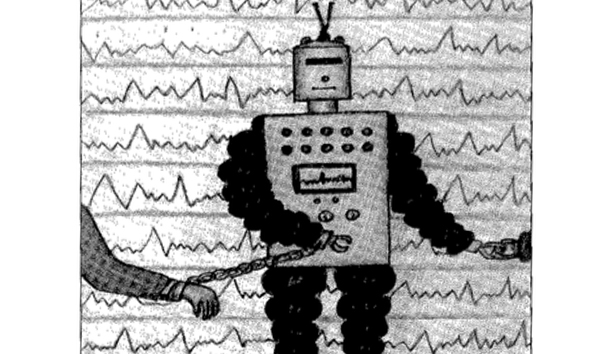

For Dick, the question then becomes whether people are able to build those bonds, with each other and with the divine, or whether they will become entirely mechanized. The key ingredient here is empathy, and in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? the characters recognize the capacity for that emotion as the dividing line between human and machine. The novel’s hero. Rick Deckard, is a bounty hunter; his job is to track down and kill escaped androids. But soon he finds himself empathizing with his victims. To do his droid-exterminating job, he must become more android-like himself.

This is a recurring moral dilemma in Dick’s books: the functionary who must choose between being human or mechanically serving the state apparatus. In three of his most remarkable novels, that functionary is a police officer. In Do Androids Dream?, the officer is Deckard. In Flow My Tears, he is Felix Buckman, a police chief in a near-future totalitarian society. And in Dick’s best book, A Scanner Darkly, he is Fred, an undercover cop searching for the source of a debilitating street drug called Substance D. When undercover, Fred is Bob Arctor, a free-spirited hippie who fits in with the people he is investigating by also using Substance D. When not undercover, Fred wears a “scramble suit,” which protects his identity by making him look like a vague blur. As the novel progresses, drug-induced brain damage exacerbates the split between “Fred” and “Bob”; soon, Fred does not realize that he and Bob are the same person, and, as he watches his surveillance tapes, he begins to suspect himself of being the drug conduit. The policeman is broken into two people: Fred, authoritarian and mechanized, devoid of identity; Bob, very human but dwindling away. Dick wrote many stories about androids, but it was this novel, without a single robot in it, that most starkly portrayed the dichotomy between man and machine.

Fred lacks more than empathy. He lacks will. As he chats with a colleague after hours of watching surveillance tapes, it becomes clear how much Fred’s identity is determined by his bureaucratic role:

“I would never hang around with creeps like [Bob and his friends],” Fred said. “Saying the same things over and over, like old cons. Why do they do what they do, sitting there shooting the bull?”

“Why do we do what we do? This is pretty damn monotonous, when you get down to it.”

“But we have to; this is our job. We have no choice.”

In a 1972 speech, Dick suggested that becoming “an android, means . . . to allow oneself to become a means, or to be pounded down, manipulated, made into a means without one’s knowledge or consent—the results are the same. But you cannot turn a human into an android if that human is going to break laws every chance he gets. Androidization requires obedience. And, most of all, predictability.” For Dick, then, just as the appearance of humanity can be negated by the reality of robotic conduct, the appearance of repression can be negated by the reality of human rebellion:

The totalitarian society envisioned by George Orwell in J 984 should have arrived by now. The electronic gadgets are here. The government is here, ready to do what Orwell anticipated. So the power exists, the motive, and the electronic hardware. But these mean nothing, because, progressively more and more so, no one is listening. The new youth that I see is too stupid to read, too restless and bored to watch, too preoccupied to remember. The collective voice of the authorities is wasted on him; he rebels. . . . He merely gets out of the way when it threatens, or, if he can’t escape, fights back. When the locked police van comes to carry him off to the concentration camp, the guards will discover that while loading the van they have failed to note that another equally hopeless juvenile has slashed the tires. The van is out of commission. And while the tires are being replaced, some other youth siphons off the gas from the gas tank for his souped-up Chevrolet and has sped off long ago.

This is Dick at his most countercultural, and to some extent his least convincing. Is a young, ignorant criminal really the best symbol of humanness? He may be unpredictable, but is he empathetic? As Dick’s biographer Lawrence Sutin has remarked, “the celebration of random rip-offs as the means of warding off centralized oppression may not convince readers who live in crime-ridden neighborhoods.”

But Dick also had a conservative side, represented by his strong (if heterodox) religious devotion, his distrust of large bureaucratic structures, and his longtime anti-abortion stance. In the last decade of his life, as he finally began receiving substantial amounts of money for his writing, Dick donated thousands of dollars to pro-life causes. He also wrote “The Pre-Persons,” a powerful story in which parents can abort any child under 12. Yet both the speech by Dick-the-hippie and the story by Dick-the-conservative are recognizably the work of the same man—both, in fact, were produced during the same period of his life. The first endorses rebellion, no matter how nihilistic, against a soulless apparatus of power; rebellion, at least, is human. And the story denies the government the right to define who is a human being, arguing that this will only produce a totalitarian system akin to the one the juvenile delinquents in the speech are rebelling against. One need not be pro-vandalism—or pro-life, for that matter—to approve of the underlying point.

Throughout his 30-year career, Dick wrote about what it means to be human in an increasingly artificial world, and about the real connections that stay firm as the state cracks down and the universe turns to maya. Today, long after his death, his stories seem more relevant than ever—prompting a rather Phildickian closing thought. In Ubik, several characters appear to survive an accident in space but are constantly confronted with messages from a man they believe has died, divine notes hidden in advertisements and scrawled on bathroom walls. Similariy, Dick has been dead for 15 years, yet his presence in the culture continues to grow unabated. In the media-saturated, paranoia-ridden world of 1997, a time of simulated men and lifelike machines, Dick’s tales might be taken as a message from the deceased author, a crude couplet from Ubik:

Jump In The Urinal And Stand On Your Head.

I’m “The One That’s Alive. You’re All Dead.

This article was originally posted in Chronicles May 1997 issue.

Jesse Walker is the managing editor of Reason and author of Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America.

Leave a Reply